Transformation of Female Gender Roles in Modern Japan

Items of Interest

Women’s gender roles in Japan have seen a transformation from the early modern Tokugawa Period through the modern period of World War II. Fukuzawa Yukichi played an important role in helping these gender roles progress from the Tokugawa Period to the Meiji Restoration and beyond. During this span of time Fukuzawa helped set the groundwork for feminists in Japan. He, along with others, helped female gender roles evolve to a modern point.

It is important to have some political background of each historical period to understand how female gender roles fit in. Also, having some comprehension of male gender roles during each period will be of assistance. Furthermore, understanding the setting of each period will provide a setting for the interaction of both roles.

The first period, the Tokugawa Period, is referred to as the early-modern period and stretched from 1600 to 1868. This period, “witnessed a regulated, efficient, and predictable bureaucratic performance that became a conscious and articulate part of Japanese politics.” Bureaucratic performance, mainly exhibited by the samurai class, was largely dictated by the political structure of the Tokugawa Period.

The basic political structure of the Tokugawa Period was hierarchical. The decentralized government, called bakufu, was a bureaucratic system. Feudal lords or barons, known as daimyo, were the ruling class of the han, or land, who were protected by the warrior class known as samurai. The power of the bakufu, “allowed daimyo to remain as lords of han domains, of which there were about two hundred fifty of varying types and shapes, and within which the daimyo retained administrative authority in judicial, fiscal, agricultural, and educational matters.” Land was granted by the bakufu to the many daimyo based on the loyalty of the daimyo in the time leading to the Tokugawa Period. Thus, the daimyo became the only ones who could have land. This was the beginning of a new period in Japanese history. The, “mechanical distribution of power and wealth was accompanied by a drastic redefinition of previous political and social history.”

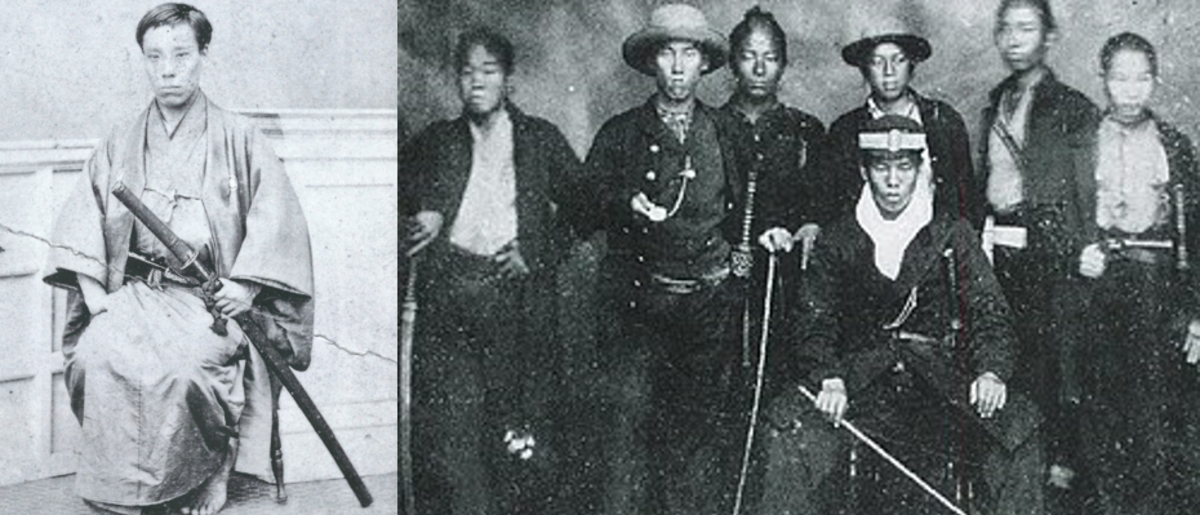

Additionally, the daimyo had samurai to protect their lands and wealth. The samurai, who were all men, were an economic and political threat to the bakufu due to the large numbers who had entered this class. Classes such as merchants or farmers did not pose a threat to the bakufu but the samurai did. Therefore, the samurai were offered a choice of status or land. Most samurai chose status and lived in cities. This choice led samurai to be, “not so much a loyal fighting man with landed interest to defend, but a bureaucrat serving in cities, living apart from the land, and receiving a stipend for his service.” This then led the warrior class to become members of an, “urban bureaucratic elite,” group. Samurai were an educated group that became directly loyal, not to the bakufu, but to the daimyo. Consequently, samurai and their principles played an integral part in the Tokugawa Period.

Many of the politics of this period were based on the philosophy from Chinaknown as Confucianism. The ideas of Confucianism, “gained creative use and expression in a divergent political context, thus playing a decisive role in the shaping of a modern society.” Confucianism is based, largely, on principles.

In reference to the samurai, Confucianism can be found to have influenced their social organization. This organization, known as,

The ie encompassed politics, blood, and economics: It perpetuated political status and territory, assured genealogical continuity and hence consistency in the social content of aristocracy, and minimized the dispersion of available wealth.

This ideology was also applied to the politics and bureaucracy of the samurai class. Confucianism supplied the samurai with a framework that influenced their daily life. Based on the ie they became loyal to the daimyo that they served.

Also, samurai were taught to be serious and faithful. Confucianism influenced the samurai through, “its teachings of benevolence, loyalty, etiquette, wisdom, filial piety, brotherly love, loyalty to the master, and faithfulness to friends.” All of these teachings of Confucianism became respected values for the samurai.

Confucianism also had a wider effect on the male and female gender roles in Tokugawa Japan. To some people in the Tokugawa Period, Confucianism provided a way to characterize men and women in the form of yin-yang. The theory of yin-yang claims that women are yin and men are yang. Yin relates to the moon and the earth while yang relates to the sun and the heavens. This belief meant that, “one is high and the other is humble, and there are many men who take this idea as the absolute rule of nature.” This is a good base to show how men of this era believe that women were subservient to men.

Also, the Tokugawa Period saw a conflict in male and female “likeness”. This was due to the surfacing of the Shingaku movement of the early 1700’s. Although there were two distinct sexes and genders there was not much of a difference in the likeness of each sex. For instance, “male Kabuki actors…performed ‘female’ roles, sometimes offstage as well as on.” The bakufu limited women to holding jobs that followed, “traditional manners and customs.” This meant that women could do hairdressing for the Kabuki theater, for example, but not any acting.

In addition, there were writers during the Tokugawa Period who used the pen to criticize women. In Kaibara Ekken’s 1672 book entitled ‘Onna Daigaku’, he, “proclaimed that female genitalia, while necessary for reproduction of male heirs, were linked to dull-wittedness, laziness, lasciviousness, a hot temper, and a tremendous capacity to bear grudges.” Obviously, Kaibara felt that women were mentally inferior to men. He also implied that men have better control of their emotions. Kaibara seemed to indicate that men were able to follow the Confucian ideals while women were not.

Later in the Tokugawa Period, more written works attempted to classify women’s gender roles. Around 1700 Kaibura wrote “Woman (Status Of)” and proclaimed many rules for women to follow. Kaibura wrote that women did not have a lord, or daimyo. Their lord was their husband. Women should follow their husband’s instructions and remain obedient to their spouse. It seems clear that Kaibura had still not changed his perceptions of women’s sexual and gender roles. Unfortunately, he was not the only man who felt this way.

A story that clearly illustrates the importance of sex and gender roles in the Tokugawa Period was written in the 1830’s. The story is about a girl named Take who cut her hair so that she could look like a boy. Her new male name became Takejiro. Initially after becoming Takejiro, “the innkeeper who employed her…raped her, ostensibly to make Take/Takejiro aware of her female sex.” The innkeeper impregnated Take and she eventually suffocated her baby when it was born. Take was then, “charged with having committed the newly coined crime of ‘corrupting public morals’…by dissociating sex from gender.” Women in the Tokugawa period had guidelines to follow and if they strayed from them they were punished. The men in this society found women to be dangerous. In accordance to Kaibara’s writings women were considered to be second-rate citizens because of their anatomy.

One man who attempted to ‘resocialize’ women was Tejima Toan. He established lectures and seminars in the late 1700’s. Toan preaches that, “females must be female-like, and males male-like; any mixup be quickly corrected.” He felt that the women should be aware of the differences between men and women.

Later, in the 1800’s, the Tokugawa government faced some instability. Aizawa Seishisai recognized a, “structural inflexibility of the bakufu,” that led him to write Shinron . This book brought up many problems that the bakufu were unable to remedy on their own. They include, “agrarian uprising, fiscal chaos, uncontrolled commercialism, [and] the impending crisis in seclusionism.” Along with domestic problems, Aizawa felt that there was a threat from the West. Aizawa was, “sentenced to house exile,” for his writings. However, Aizawa’s efforts were not in vain.

A daimyo named Mita Nariaki was influenced by Aizawa’s words. Mita came to believe that the voice of the daimyo should be heard on a national level. Furthermore, his questioning of the decision making of the bakufu came across as criticism. Unfortunately, Mita was unable to influence other daimyo as Aizawa influenced him. The result was Mita was banished from Edo and required to, “remain in house exile until advised otherwise.”

Eventually, Oshio Heihachiro, a bakufu official from Osaka, was able to find a way to turn a samurai’s loyalty against their daimyo. He realized that a samurai’s loyalty “could be turned into a denunciation of existing politics.” Oshio became a man trying to ‘save the people’. He led an attack on bakufu troops in Osaka in 1837. There were, “famine-stricken farmers in the area,” and Oshio felt a rebellion would quell their situation. The rebellion failed; one fourth of Osaka was burned down. However, the failed rebellion resulted in Oshio becoming a, “cultural hero.” His idealism became transformed from ‘saving the people’ to, “protecting the country.”

Oshio’s actions led to the emergence of a group known as the ‘loyalist faction’, orkinno ha . The loyalists came from all over Japan and consisted of, “masterless samurai, or ronin.” One loyalist who became a prominent leader was the poet Yoshida Shoin.

Yoshida wanted the bakufu overthrown and the ordinary men of the countryside to have a say in their own government. He realized that, “to arouse these stalwarts of the countryside only dedicated leadership and an inspiring example of the true warrior spirit were needed.” Since Yoshida was a poet he was able to clearly write passages that showed his views about leadership. For instance, he wrote a simple line that serves as a way to inspire the common man. Yoshida writes, “To consider oneself different from ordinary men is wrong, but it is right to hope that one will not remain like ordinary men.” He implies that being a common man does not make a person less of a man, but being content with that low status is unacceptable.

There were also anti-Confucianism implications by Yoshida. In an excerpt entitled ‘On Being Direct’ he writes:

The mind of the superior man is like Heaven. When it is resentful or angry, it thunders forth its indignation. But once having loosed its feelings, it is like a sunny day with a clear sky: within the heart there remains not the trace of a cloud. Such is the beauty of true manliness.

Letting loose with emotions seems to contradict the Confucian idea discipline and acting like a gentleman. In Confucius’ book ‘The Analects’ he writes, “The Master said: ‘The gentleman is always calm and at ease; the little man is always worried and full of distress.” Obviously, Yoshida’s writings directly conflict with those of Confucius. Therefore, it is clear the Yoshida is attempting to influence a breakaway from Confucian ideas as well as the Tokugawa government.

Yoshida’s influence led to rebellions against the bakufu. These rebellions, in turn, led to the bakufu becoming unstable. Also, Yoshida planned on assassinating the man who was to, “secure the emperor’s approval for a treaty with the United States.” Unfortunately for Yoshida, his plans were discovered and he was arrested. In Edo, in 1859, Yoshida was executed. Najita wrote, “Perhaps most significant, rebellion in the cause of a wider loyalty acted as a decisive catalyst in the political development of the 1860’s.” The end of the Tokugawa Period was in sight and this was the result of the loyalist rebellions.

Eventually, these rebellions led to a restoration of the emperor in Japan. In 1868 the Meiji Emperor was restored to his throne. Although only sixteen, the new emperor took his throne in the capital city of Edo, which was to be renamed Tokyo. The Tokugawa government had become the restored Meiji government and thus the modernization ofJapan began.

The loyalists had succeeded in ending the reign of the bakufu. Their new challenge was to get power to be shared. Under the new Meiji government the Imperial Charter Oath was introduced. It proclaimed, “All affairs of the state…shall be determined by public discussion.” No longer was the voice of the people silenced. Furthermore, restrictions on class mobility were to be lifted. This allowed, “everyone to freely move, buy, sell, educate himself, and choose an occupation without regard to previous status and geographical location.”

Although the government had changed, its political suppression of women did not. Women were still excluded from politics during the early Meiji period. In 1887 the Ministry of Education sponsored a work entitled “The Meiji Greater Learning for Women” that proclaimed, “that ‘the home is a public place where private feelings should be forgotten.” Furthermore, The Law on Associations and Meetings enacted in 1890, prevented women from, “attending political meetings or joining political organizations.” This was done not because women were, “physically, mentally, or morally incapacitated,” but because women were more valuable socially. Women were necessary to run the house and to help school the children. They had to be prepared to jump in and assume the role of house leader if their husband had to go to war. Basically, the government wanted women to assume a role, but not one involving politics.

Meiji policies that were put together became based on two assumptions. The first was, “That the family was an essential building block of the national structure.” The second assumption was, “That the management of the household was increasingly in women’s hands.” This meant that a good wife would be one who would be of service to society as well as to her family.

The ideal of the ‘Good Wife, Wise Mother’ arose from these policies. The government wanted women to be involved, “through their hard work, their frugality, their efficient management, their care of the old, young, and ill, and their responsible upbringing of children.” Even though women had responsibility on the home front they were unable to be politically active. The state policy of the early Meiji Period “placed much more importance on a woman’s responsibilities as wife than on her function as mother.”

In the early 1900’s The ‘Good Wife, Wise Mother’ policy was prominent in elementary education. The Education Ministry, in 1900,

Issued guidelines on training appropriate to each gender, which included admonitions that girls be educated in feminine modesty…but there was no special emphasis on motherhood.

This was done largely in response to the increasing number of girls in the elementary schools.

In addition to the Education Ministry, the Home Ministry implemented a majority of the policies that the Meiji government imposed upon women. The Home Ministry was the part of the government that ensured national policy was enforced on a local level. For example, the Home Ministry was responsible for controlling the police who made sure women that women were not politically involved. They also were, “responsible for community organizations for adolescents and adults.”

Another group that was affected the Meiji government’s declassing was the samurai. Once the daimyo were dissolved the samurai were left without masters. Additionally, the samurai were forced to give up their swords and to stop wearing their hair in a topknot. Many of the loyalist leaders objected to the way that the samurai were treated. They felt that dissolving the bakufu was enough to unite the country and the samurai should be left alone. The only consolation that they received was that they were now called, “shizoku, or ‘former samurai”

Arguably the most influential person who wrote about the role of women in the Meiji period was one of these newly renamed shizoku. A man named Fukuzawa Yukichi saw the Meiji Restoration as a new beginning. He wrote, “Unexpectedly came the Restoration, and to my delight Japan was opened to the world.”

Fukuzawa Yukichi was a man who passionately addressed roles of women. He, “was the first influential advocate of women’s rights in modern Japan,” who also worked to liberate women from their, “traditional ideas and practices.” Fukuzawa was raised in a household that consisted mostly of women, including three older sisters. His childhood may explain his empathy for women. Since he was around many women they may have led him to become, “pampered and spoiled with affection...” and thus more sensitive and understanding toward gender roles of women.

Moreover, Fukuzawa wrote an autobiography. This book gives some background, and thus insight, into why Fukuzawa had strong beliefs. He wrote about the philosophy that he learned from the ancient Chinese phrase “Never show joy or anger in the face.” This phrase taught Fukuzawa that he should, “receive both applause and disparagement politely…” This led to Fukuzawa living as a peaceful man. He claimed that he never touched a person in anger except for the one time he shook a snoring boy awake. This philosophy enabled Fukuzawa to write about the roles that men and women played in Japanese society with a clear conscience.

In addition to his mental well-being Fukuzawa was also in excellent physical shape. The only Achilles’ heel that Fukuzawa had was alcohol. He admits his, “love of drinking,” but other than that he lived, wrote, and traveled with a clear head and a sound body.

Fukuzawa wrote about the morals of men in his book entitled ‘Fukuzawa Yukichi on Japanese Women’ during the early Meiji period. He claims that he wants Japanese men to improve their moral behavior. Fukuzawa wrote, “I advocate just three principles.” The first is that younger men should get rid of the habits that are deemed obnoxious. Second, Fukuzawa wanted the men who were; “unable to resist their urges…[to] keep their acts as the greatest secrets of their lives.” Finally, he wanted the men to realize that their customs are revolting and they should, therefore, be avoided.

Furthermore, Fukuzawa’s observations about prostitutes and the men who visit them were very clearly written out in the same book. Fukuzawa felt that men had two sides to them—one was a civil human being and the other was animal-like. He wrote, “A man is human when he is dressed properly in clothing, but when naked, he is a beast.” Fukuzawa felt that men were able to keep the animal in check by going to prostitutes.

He also realized that there were a large number of single men who found prostitution to be a necessity. These men were most likely single, according to Fukuzawa, because, “Poor men for their poverty cannot support their wives…” Fukuzawa rationalized that if these men were able to earn more money to support a family there would be a significant decrease in prostitution.

Fukuzawa knew that most people with morals would have banned prostitution, but he felt it was a necessary evil. He believed that, “Prostitution was indeed lowly, ugly, and for the person who practices it, must be both physically and spiritually degrading.” Nonetheless, Fukuzawa did not feel that prostitution should be eliminated. He believed that society would crumble without these women. Furthermore, Fukuzawa wrote that, “We need to recognize these women as great benefactors who, at great pains to themselves, are serving the whole of society.” Fukuzawa felt that without the prostitutes men would expose the ‘beast’ from within. He indicated that sexually oriented crimes, or even violent crimes, would rise if the prostitutes were forbidden.

Although Fukuzawa did not want prostitution banned he did want the Japanese men to show some restraint as well as responsibility. He sensed that the West would look at Japan as being morally bankrupt. Fukuzawa felt, “That, unless Japanese curbed or at least put a veil over their loose sexual conduct, Westerners would criticize, ridicule, and scorn them.” It was apparent that he was quite concerned with how the West viewedJapan. Many of the Japanese government officials fit into the category of ‘loose sexual conduct’. This troubled Fukuzawa to the point that it became one of the main reasons that he declined to work for the government.

Undoubtedly, Western influences on Fukuzawa begin to show up during this moral dilemma. Fukuzawa’s concern for how the West views Japan appeared when he compared the West with Japan. He evaluated the clothes, the food, the homes, and even the gender roles. For example, he noticed that Western homes have mirrors in every room. These mirrors were necessary since Western clothes have many buttons. In reference to food, Fukuzawa wrote, “It has to be remembered that slurping is bad manners, even when you drink tea.” The differences that Fukuzawa noticed between Japan and the West became influential, to some degree, in how he viewed Japanese society.

A trip to America supplied more Western influence onto Fukuzawa, along with the opportunity to be able to relate to a Japanese bride. On his trip he was unable to locate an ashtray to put his cigarette out in. He wrapped the cigarette and its ashes in tissue paper and stuck it in his sleeve. His sleeve began to smoke and his clothes quickly caught on fire. He was so embarrassed that he wrote, “After all these embarrassing incidents, I thought I could well sympathize with the Japanese bride.” He felt, that like a bride, he was welcomed to a home with open arms and made to feel comfortable. However, again like the bride, Fukuzawa attempted to look comfortable but made mistakes that kept embarrassing him. He summed up his experience by writing, “But on arriving in America, I was turned suddenly into a shy, selfconscious, blushing ‘bride.’”

Fukuzawa was not well received by all, and he did have critics. Tetsuo Najita criticized Fukuzawa in his book ‘Japan’. Najita claimed that Fukuzawa was interested in, “individual autonomy…[that] rests on the rational pursuit of self-interest.” The author goes on to condemn Fukuzawa for not really being a supporter for natural rights. Najita suggested that Fukuzawa, “stressed the hedonistic propensity of men as the basis of individual choice…” He also pointed out that Fukuzawa believes if men are able to exhibit self-control they will exemplify liberty. Najita wrote, “…[Fukuzawa’s] idea of ‘liberty’ was actually a psychological power to ‘endure’ that is conceptually distinguishable from the theory of natural rights.” He again indicated that Fukuzawa was not truly for a natural-right theory.

Eventually, the Meiji Emperor died in 1912 and the Meiji Restoration came to an end. The Taisho period began at this time. In addition to the death of the emperor, the new period was a result of the growth of political parties and party government. It was during this time that middle-class women entered the work force without concern from the government.

However, in the mid 1920’s the Showa Restoration replaced the Taisho period. The Showa Restoration “was not a single event involving actors espousing identical political ideas,” but it was the culmination of many events related to Japanese politics. Many people called for another restoration in the 1920’s after Japan gave in to the demands of the West. Furthermore, some Japanese were angry at how Japan lost strength in its stand against Russia. I feel that the Taisho period and the Showa Restoration can be viewed as one continuous era in the advancement of female gender roles. For example, women were granted the legal right to join political parties in 1922. Also during the 1920’s and 1930’s women laborers were able to find work while at the same time women challenge their social roles.

During the Taisho period the number of female laborers increased from the 1910’s through the 1920’s. These laborers were classified, “as urban salaried workers whose educational background and earned income…put them in the working class.” Although their numbers increased in the 1920’s, these women were still small in numbers in relation to the Japanese population. During the mid-Taisho period there were only 3.5 million women working out of the entire population of 27 million women.

One person who attempted to rationalize why women had the new opportunities for work was Margit Nagy. She concluded in her piece “Middle Class Working Women During the Interwar Years” that there were three reasons why the female middle-class labor force increased. She wrote that, “Three basic reasons explain the increase in middle-class working women: economic necessity, awakened women’s consciousness, and job availability.”

First, economic necessity was a result of middle class families spending most of their money on day-to-day needs. This led to many young women getting jobs. Secondly, many women found employment to be, “an expression of the women’s irrepressible aspiration for independence and self reliance.”Women began to influence the country through their awakening to society. Lastly, some single women took available jobs just to have the money. These women were in no hurry to get married and wanted to become more independent. Taking a job was the best way for these women to maintain their independence.

This redefinition of the gender role for these women was largely met with ambivalence. However, one person was able to find a positive take on the roles. Murakami Nobuhiko suggests that there was tolerance for women during the interwar years. She notes during this time period that magazines contained articles about employment for women. According to Nobuhiko, these factors, “made it possible for middle-class women to seek jobs—something that their mothers and grandmothers could not have done except in teaching.” It appears, then, that these women were trailblazers for other working middle-class women.

Furthermore, women made another step forward in the form of the ‘Modern Girl’. In “The Modern Girl as Militant” the Modern Girl is described as a, “glittering, decadent, middle-class consumer who, through her clothing, smoking, and drinking, flaunts tradition in the urban playgrounds of the late 1920’s.” This description obviously contradicts the previous perceptions of how women acted.

Additionally, in 1924 Kitazawa Shuichi describes the Modern Girl in the magazine ‘Josei’. She claims that the Modern Girl does not want to be enslaved by men, but at the same time she does not support any more women’s rights. Also, “Kitazawa saw a reconstruction of gender,” that was the by-product of this newly animated women.

Furthermore, the physical appearance of the Modern Girl “was defined by her body and most specifically by her short hair and long, straight legs.” She wore Western clothes and dressed in a sexually attractive way. The Modern Girl also flirted with men, although not all men were receptive to these flirtations.

The magazine Shincho published ten characteristics of the Modern Girl in 1928. The people who contributed to the article came up with the following attributes of the Modern Girl. They believed that, “(1) she was not hysterical; (2) she used direct language; [and] (3) she had a direct, aggressive sexuality…” Also, these contributors realized that the Modern Girl could be poor since clothes were no longer expensive. The Modern Girl was additionally not a promiscuous person. Also, “she was liberated from the double fetters of class and gender…” Also, the Modern Girl would approach men if she were in need of train fare. This was possible because she had a freedom of expression that was evident in the fact that, “she was an anarchist…” Finally, she found her counterpart, the Modern Boy, to be worthless.

Most of these characteristics surfaced due to policy changes in the government. Many changes, with regards to a woman’s place in the family, occurred to the Meiji Civil Code. These changes meant that women no longer needed parental consent to get married and they had the ability, “to manage their own property.” They also had expanded rights as a parent and the ability to get a divorce easier. Furthermore, the ban on women from politics was lifted in 1922. These new advances for women allowed the Modern Girl to be, “truly militant.”

Although the Modern Girl represented an up to date woman she was viewed as a menace to Japanese traditions by the government. The poor economy helped lead the Modern Girl to find changes that were not Japanese. Some even wrote in the newspapers that the Modern Girl was “un-Japanese and therefore criminal.” This role of the Modern Girl was modified not too long after her initial appearance.

The 1930’s and 1940’s saw another role taken on by Japanese women. During the pre-war and World War II years women were essentially reduced to the role of childbearing. In the late 1930’s many women were, “relied on…for daily wartime activities, such as food rationing and fire drills in the event of air raids.” However, having large families was the main role for women.

Also, propaganda was used to encourage women to send their sons to war without apprehension. Slogans such as “Be Fruitful and Multiply for the Prosperity of the Nation” were meant to persuade women to do this without a second thought. These slogans also wanted to encourage the women to produce large families that would supply the manpower for the Japanese war effort.

Additionally, in 1940 and 1941, the government issued mandates. These mandates were meant to prevent the unhealthy from reproducing while barring the healthy from using birth control. “The sterilization of those identified as having hereditary diseases, and the prohibition of birth control for the healthy,” was the main intention of the mandates. Again, this would provide the Japanese armed forces with able and ample manpower. The pressure was on healthy women to have larger families.

When Japan entered World War II in 1941 the role of women became essential to the war effort. Young single women were the main target of the government used to assist with the war effort. These women worked in the industrial sectors such as munitions. The lack of pay equal to men led to, “the abuse of women in the workplace.” Eventually, single women up to the age of twenty-five were drafted toward the end of 1941. The government wanted these women to help with war duties in the neighborhoods, schools, and workplace. They, “were also obliged to do thirty days’ factory work a year…” However, by 1944 most of these women did not respond to the draft notices. Many chose to stay at home to care for their family instead of going to work in poor factory conditions.

After the war, most women who held the jobs in the factories were fired. However, their entry into the workplace helped alter their gender roles on the home front. Women were eventually able to share responsibilities with their husbands. This allowed Japanese women to continue the evolution of their gender roles and responsibilities.

From Tokugawa Japan through World War II women were in constant development of their gender roles. These roles have evolved from housewife all the way to a radical change such as the Modern Girl. When the Tokugawa Period began women could not be involved in politics, but by the end of World War II they were already politically active. The writings of Fukuzawa, and others, helped pave the way for these changes in gender roles.

Sources:

Yukichi Fukuzawa "The Autobiography of Yukichi Fukuzawa " (Columbia University, 1981)

Tetsuo Najita "Tokugawa Political Writings " (Cambridge University Press, 1998)

Gail Bernstein "Recreating Japanese Women " (University of California Press, 1991)

Donald Roden "Schooldays in Imperial Japan: A Study in the Culture of a Student Elite " (University of California, 1980)